This post is the CliffsNotes® version of all the remaining posts. If you want to go down the rabbit hole on any particular topic, just click on the link. If you just read this, it will tell you all you need to know. Reading my blog posts will make more sense if you have already read Charles Herrick’s book, Back Into Focus, and/or Allan Coleman’s blog post on his website, Nearby Cafe.

The Orthodox

Robert Capa was born in Hungary in 1913 and died in Indochina in 1954. He became one of the greatest photographers of the Twentieth Century and was known at one point as “The Greatest War-Photographer in the World.”

Arguably, he made his best known photographs on D-Day, June 6, 1944 on the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach, the section with the highest casualty rate of the entire invasion that day, roughly 3,000 of the 5,000 total on five beaches. Nearly 140,000 allied troops landed in total.

Capa said he wanted to go in with the very first wave, but the evidence shows that he went in about an hour after the initial assault troops, when the beach was still hot with withering machine-gun fire, artillery and mortar rounds from a fortified and determined enemy. Field Marshall Rommel had hardened this part of the Normandy coast to repel an invasion by the Allies.

He probably did not intend to disembark from his landing craft, an LCVP, from the USS Chase. His job that day was not to go inland and fight. His job was to get pictures of the invasion and return them to the Life magazine offices in London as soon as possible. The Life European picture editor, John Morris, needed to make an absolute deadline for publication in the next issue of the magazine. But first the film had to be processed and cleared by censors.

Robert Capa’s Negative 29, depicting soldiers from the 16th Regimental Combat Team disembarking at Easy Red sector on Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944.

As Capa stood on the ramp of his LCVP, taking pictures of men wading through the water, the boatswain suddenly kicked him in the backside so the ramp could be raised and the boat withdrawn. Capa found himself in the water.

AI-generated image of Robert Capa being kicked off an LCVP. I couldn’t seem to train the software to show an LCVP.

The sequence of events for the next 60 to 90 minutes is not clear. Capa wrote an admittedly embellished account of his experience. He said he moved between various objects in the water, making his way toward shore and photographing the men trying to get to the beach. Once on the beach, he exposed a second roll of film in his second camera, for a total of two rolls on Easy Red.

As he started to change out his film in that camera, among the machine-gun fire and the mortar explosions, among grotesquely mangled human remains and screaming men, panic paralyzed him. He looked out to sea, saw a newly arrived landing craft, got up and ran for it, holding his cameras over his head to prevent them from getting wet. A sailor on that ship recognized him coming toward them. Captains were forbidden to pick up any men, but since he was a famous civilian correspondent, they allowed him to board.

He ultimately made his way back to the English port of Weymouth where he handed his film to a courier, who took it to London. His job thus finished, Capa changed clothes and boarded another vessel headed for Normandy, where he followed the troops in to Paris.

In London, the film had to be handled by military censors before it was delivered to the Life offices where Morris set his staff to work quickly so that he could make his deadline. He received a message from the darkroom that the pictures were “fabulous,” but a short while later an adolescent darkroom assistant, Dennis Banks, told Morris that he had ruined the film by heating the drying cabinet too high. He said the heat caused the emulsion to melt, destroying any images it might have contained.

Morris was mortified at the “grey mud” appearance of the ruined roll, but also relieved that some of the images on the end of the first roll remained. The exact number of images is either 10 or 11, and one of those is missing, negative 37. That’s the Face in the Surf image at the top of this post. Morris doesn’t clearly recall what happened to the second ruined roll, so it has become known as the “lost roll.” The surviving pictures have become known as “The Magnificent Eleven,” (even though it’s probably just ten).

That is the story that Robert Capa and John Morris recounted many times over many decades.

Robert Capa’s surviving pictures from D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Enter Allan Coleman

In 2014, the photo critic, Allan Coleman, challenged this narrative. Prompted by a guest post on Coleman’s blog by J. Ross Baughman, a Pulitzer Prize recipient, that strongly questioned the story, Coleman started an investigation that is still ongoing. Others have joined Coleman in his project. Charles Herrick brought a military perspective to the story and performed detailed research on the events of that day. Herrick concluded that Capa was at Omaha Beach for only 20 to 30 minutes maximum, photographed for only 6 minutes, and that he never made it to shore.

Herrick and Coleman concluded that Capa fabricated the entire portion of his story about the second roll. They concluded that Capa chickened out, deserting the scene ignominiously. He cowered and ran home as fast as he could with a paltry showing for the world’s greatest war photographer. Ashamed and embarrassed, Capa and Morris concocted the above fiction about the beach and the second roll and the teenaged darkroom assistant and the ruined emulsion. Capa had risked his life for those pictures, and some kid had ruined them.

Somehow, Capa and Morris were able to coerce all the Life staffers in London and the military censors to go along with this story, and keep the secret until the end of their lives, even after the war and after they had returned to their homes and families. The story was passed down through the generations who continue to propagate the same fiction. The people constructed a complex and vast financial network centered on this fiction, resulting in the enrichment of nefarious characters, such as curators and CNN anchors.

Injustice

Coleman refers to these despicable people as “The Capa Consortium.” I refer to Coleman and his collaborators as “The Coleman Clan.” That’s Clan, not Klan.

The great lie has obviously enraged the Clan, because they are unable to dismantle the lie dispassionately. Their critique rhetoric is laced with cynicism, sarcasm, insinuation, and anger. Coleman called the 97-year-old Morris “morally and ethically corrupt” and considers Capa a self-aggrandizing charlatan. Herrick loathes Capa for his moral failures and his mediocre, at best, photography. Baughman considers Capa a cowardly dandy.

I admit that I was somewhat convinced on my first reading of the blog posts and Herrick’s book. However, I was so disgusted by their disrespectful language that I couldn’t get their thesis out of my head, so I read it all again. Then it dawned on me that their arguments were specious.

The first thing that popped out to me was their naïve experiment where they used a modern single lens reflex camera to mimic what Capa would be able to see through his 1936 rangefinder camera, to test the validity of a story later told by a fellow soldier.. Looking through the lens, they “proved” that he could not see enough detail through his “telescopic lens” to discern details on a distant figure.

Well, of course not. The viewfinder on the rangefinder on Capa’s Contax was separate from the lens on the camera. Not only is it separate, it is tiny and dark, and only gives the field of view of a normal 50mm lens. It would have been impossible for Capa to have seen the enlarged, telephoto view of his lens through the separate viewfinder. This little bit of ignorance did not stop them from high-fiving each other, however. They viewed their experiment as further evidence of Capa’s mendacity.

What bothered me the most, however, was the disrespect and dismissive manner in which the Clan dismissed the stories of eye-witnesses and children of those eye-witnesses, when their stories did not comport with the story the Clan had concocted.

So I set out to see if their logic and reasoning in the rest of their work was similarly flawed, and I found that often it was.

Ask Capa

Capa is not here to defend himself, but he can speak through his pictures. I used some high school trigonometry to calculate distances and positions of objects and men in Capa’s photographs, disproving some of the Clan’s assertions.

Robert Capa’s Negative 32 from Easy Red, June 6, 1944. Using simple trigonometric equations, I was able to calculate distances from Capa’s camera to various objects.

After calculating the distances and angles, I was able to map out Capa’s location as he made negatives 29 through 38, including how he shifted his position as he took the pictures.

Next, dissecting Herrick’a analysis of when Capa arrived at Easy Red, I found the flaws in his logic. My findings were supported by eyewitness accounts, including letters written from Normandy by a soldier who was standing next to Capa in his LCVP, and who would later become the dean of the School of Engineering at Stanford University. All of this refutes Herrick’s determination of Capa’s arrival time and duration of stay at Easy Red.

Finally, I did an experiment where I proved that the film in Capa’s second camera, which was submerged in the English Channel for 10 to 20 minutes then dried for 36 hours, could have had the appearance of “grey mud,” as John Morris described Capa’s “lost roll.”

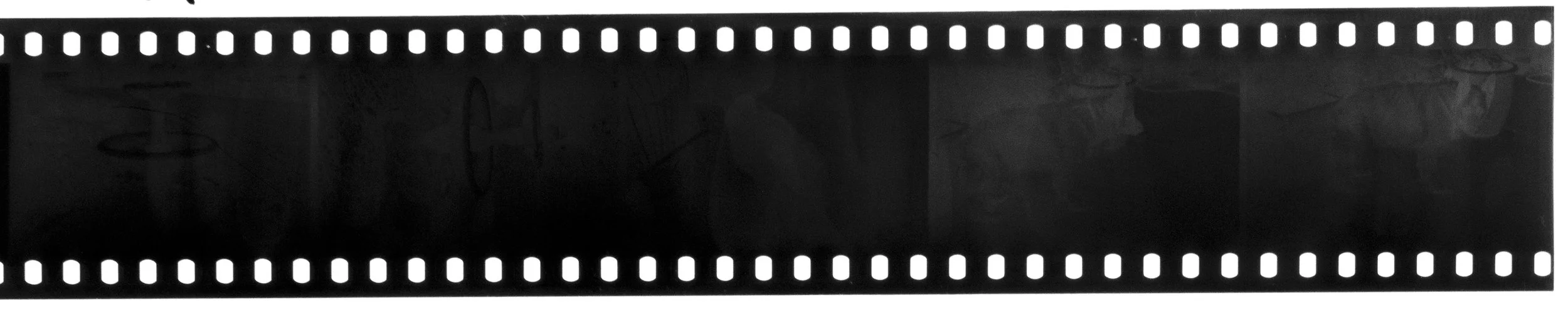

A negative strip from Kodak-XX (5222) film, immersed in 3.5% saltwater for 20 minutes, then air-dried for 36 hours and developed normally. The images are barely discernible. The negatives have the appearance of “grey mud.”

The Clan severely criticized Morris for allowing an inexperienced “darkroom lad” to process some of the most important film of the Twentieth Century. But he didn’t. I believe the film was processed by Hans Wild, who inspected the end of one roll mid development, determined that the pictures were “fabulous,” and notified Morris. He continued working on other film returned that day, and told the assistant to stick the film in the dryer with the heater turned up so that they could print the film in time for the deadline.

Dennis Banks cranked the heater to max, but when he retrieved the film from the cabinet and inspected it, he saw what you see above, and assumed this was related to the excess heat, since just prior to that Wild had declared the images to be fabulous. John Morris had no darkroom experience, so he accepted the darkroom lad’s explanation. By the time Morris could tell Capa, the prints had been made and the pictures has been published in the June 19, 1944 issue of Life magazine, and the story of the darkroom disaster was established.

Life magazine, June 19, 1944.

So, there was no fabrication of the “darkroom myth.” And since there was no fabrication of the darkroom myth, there was no reason for Capa to lie about being on the beach, or arriving earlier in the invasion than Herrick claims. The claims made in 11 years of blog posts and a 384-page book, fall flat.

At least, that’s my theory, but I think it’s better than the Clan’s theory. If you dive into the various blog posts, I am confident that you will see the precision with which I was able to determine Capa’s location while he took these pictures. You will see the cracks in their logic when determining Capa’s late arrival. You may be appalled, as I was, of their claims that Capa arrived under relatively light fire and that there was nothing heroic about his presence on Omaha Beach at all - in fact they assert he was a coward. You will learn that 20 minutes of immersion in saltwater results in negatives that fit Morris’ description of the “lost roll” on the night of June 7. And there’s a lot more.

Each of the blog posts covers a specific part of this story, so you can jump around and dig down if you want. At some point I will go through and organize the references better.

Please feel free to comment. I welcome all opinions and viewpoints, and will seriously consider them. Thank you for your interest in this topic. Please share this with your friends and colleagues.

[Ed. note: 6/1/25. I made some word changes above after publication earlier today - things I missed. I will add an editorial note whenever I make a major change to a post. I will not put a note when I correct typographical errors or grammar.]

[Ed. note: 11/12/25. Further minor clarifications made.]

ALL BLOG ENTRIES THROUGH 23rd COPYRIGHT 2025 CHARLES TIMOTHY FLOYD