So many of the conclusions reached by the Clan, especially by Herrick, are based on Herrick’s "conclusive proof" that Capa arrived at Easy Red at 0820, not 0740. Arriving at 0820, Capa could not have made it to the shingle; taken more than the known 10 images; gone in with the second wave; seen bodies and parts of bodies floating in the water; been under indirect mortar fire; faced machine gun fire from the Germans. Et cetera. None of that could have happened because Herrick conclusively proved that Capa arrived at 0820 and lied about coming in earlier to enhance the self-aggrandized world opinion of him. End of story.

Not only that, but if Capa arrived at 0740 and did all that he said he did, then he and Morris would not have had to concoct the darkroom mishap myth, and intimidate Life staff and military censors to keep the secret for the rest of their lives so that unborn people working for future institutions would make a fortune off of the deception.

One of these “proofs” that stands out as particularly egregious involves First Lieutenant William M. Kays, and his radio operator, Lenny Doyle.

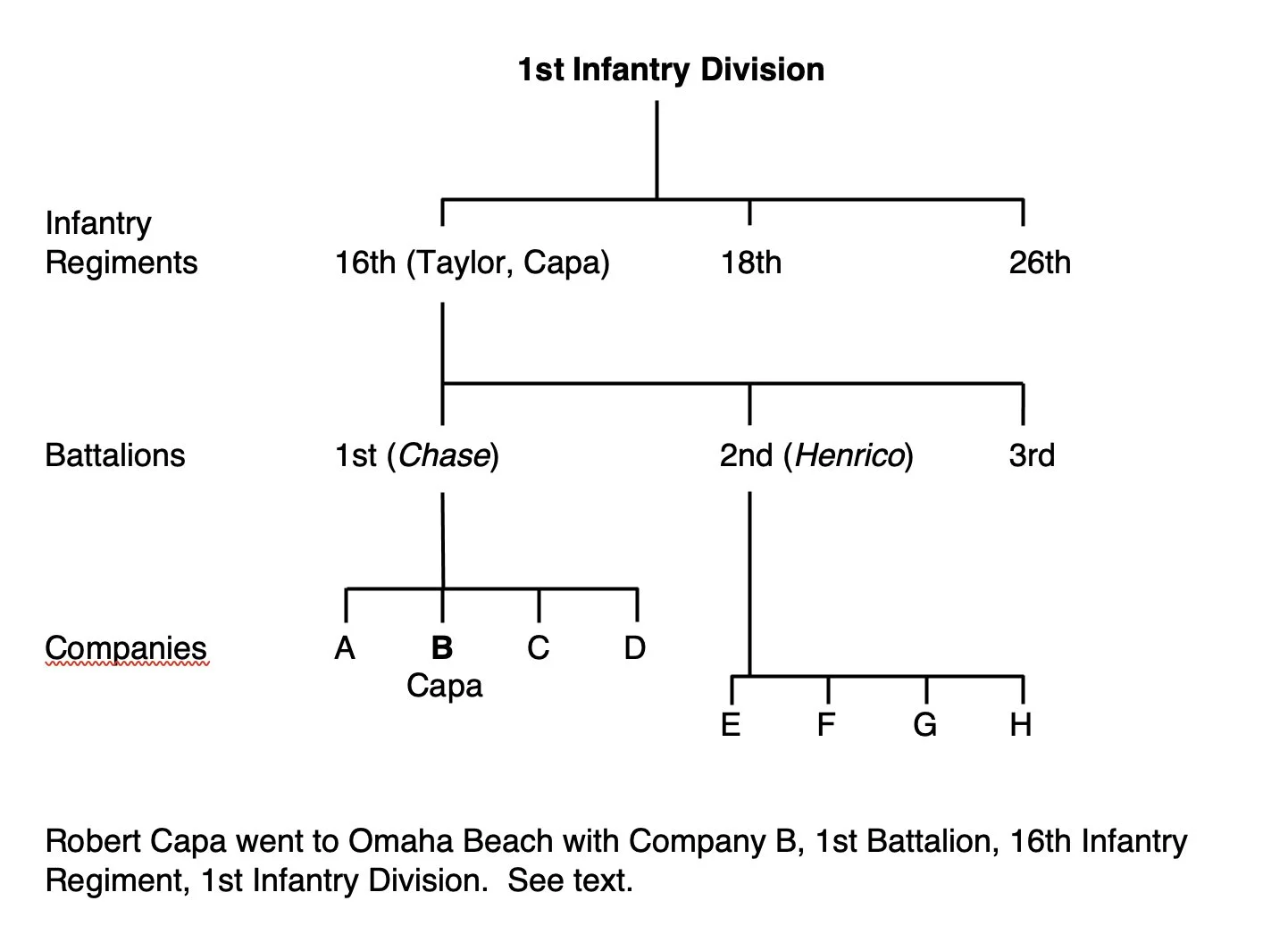

I'll let Herrick explain Lieutenant Kays' role. "Kays was the commander of a provisional engineer company consisting of two platoons attached to the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry. Those two platoons came in on three LCVPs in Wave 11, the same wave as Company B of that battalion. Also in that wave was the LCVP carrying the 1st Battalion’s commander, and Kays claimed to have ridden in on that boat." *

I will add to this the fact that, after the war, Kays finished his Ph.D. in engineering at Stanford University, where he went on to become dean of the School of Engineering at Stanford for twelve years, 1972–1984, during which time Silicon Valley developed.

In his Memoir, Letters From a Soldier, and a subsequent article,** Kays described being on the USS Chase with Capa, and riding in the back of the LCVP to Omaha Beach with Capa. He described a brief conversation with Capa in that LCVP near the beach. He described how his radio operator, Doyle, took off his radio when machine gun fire started hitting the boat and he saw men drowning. He and another soldier carried it to shore.

Kays described later seeing Capa in the water taking pictures from behind a tank.

This book, which was published in 2010, was not based on memory from events nearly seven decades earlier. Kays collated and quoted his contemporaneous letters home that his mother saved. Herrick called the letters inauthentic and, therefore, invalid in his view. That inauthenticity, according to Herrick, was a proof that Capa did not ride in with Kays. (See blog post, Depth Charge)

The story of Capa riding with Kays and Doyle was corroborated by Doyle's daughter, Maureen Doyle Sullivan, who wrote a comment on Coleman's blog, stating

"Not sure if this will be useful to you but here goes: My father, Lenny Doyle, served in the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion with the 1st Infantry Division and made the Omaha Beach landing on D-Day (he passed away in 1993). He told us that he had spoken with Capa prior to the landing, not sure if it was on the Samuel Chase or in the landing craft. I recently found this article on HistoryNet which names my father as a radio operator who hit the beach with the author (William Kays). In addition to the photos in Kays’ article, I am quite certain that my dad is one of the soldiers in one of Capa’s photos, the one that shows several soldiers lying on the sand behind a hedgehog." [*]

Coleman dismissed Ms. Sullivan's comment, stating, "Military historian Charles Herrick effectively disproved the claims of William Keys in this 2019 post here at my blog. Since Capa rode in not with the engineers in the second wave, but with Col George Taylor's staff in the thirteenth wave, your father could not have spoken with him en route to Easy Red." Coleman told Ms. Sullivan that her dad lied to her.

Coleman also labelled the Kays and Doyle stories as "stolen glamour," which he defined as "a milder corollary of the more familiar 'stolen valor' – to describe the less objectionable but still problematic tendency to exaggerate or invest entirely one's relationship to celebrated individuals, historical moments, etc."

Herrick used the term, stolen glamour, as the title of his series of blog posts, referring to the accounts from Kays and Doyle as "parasitic legends." [***]

In other words, according to the Clan, Ms. Sullivan's father lied to her about his experience in World War II, to have some of Capa's glamour rub off on him. Same for Kays. Big fat liars.

Not to mention the other two eyewitnesses to Capa's presence on the beach at 0740, Samuel Fuller and Charles Hangsterfer. Also, big fat liars.

And then there's another witness, the nameless Face in the Surf soldier, Huston Riley, who placed Capa there well before 0820. But I digress...

Let's do a little analysis to find out who, exactly, is lying.

The first deceit involves which boat Capa rode in on. Herrick found good evidence that a civilian photographer, of which Capa was one of three, was assigned to ride in with Colonel Taylor in the 13th wave, in a LCM.

The other two went with different regiments, so it's safe to assume Capa had this assignment. The other boat on that wave was a LCVP, and included the medical team. These manifests were immutable, according to Herrick. Capa couldn't change even if he wanted to.

Herrick barely mentions that Colonel Taylor switched boats with the medical team, and actually went in on the LCVP. Meaning, the manifests were not immutable, at least not for the commander.

What Herrick conveniently left out is the capacities of those two crafts. The LCM carried up to 100 people, plus crew. The LCVP carried up to 36, plus crew. Very likely Taylor prioritized his staff to ride in with him in the much smaller boat and told the photographer to fend for himself.

Capa had already said he wanted to go in with Company B in the second wave, which debarked from the USS Chase at the same time as Taylor's wave, according to US Coast Guard records. So, it makes perfect sense that he squeezed in with one of the boats in the second wave, Kays' boat. "Hey, Cap! Come with us. We'll make room!"

So far, Herrick’s proof seems far from "conclusive," but it gets worse.

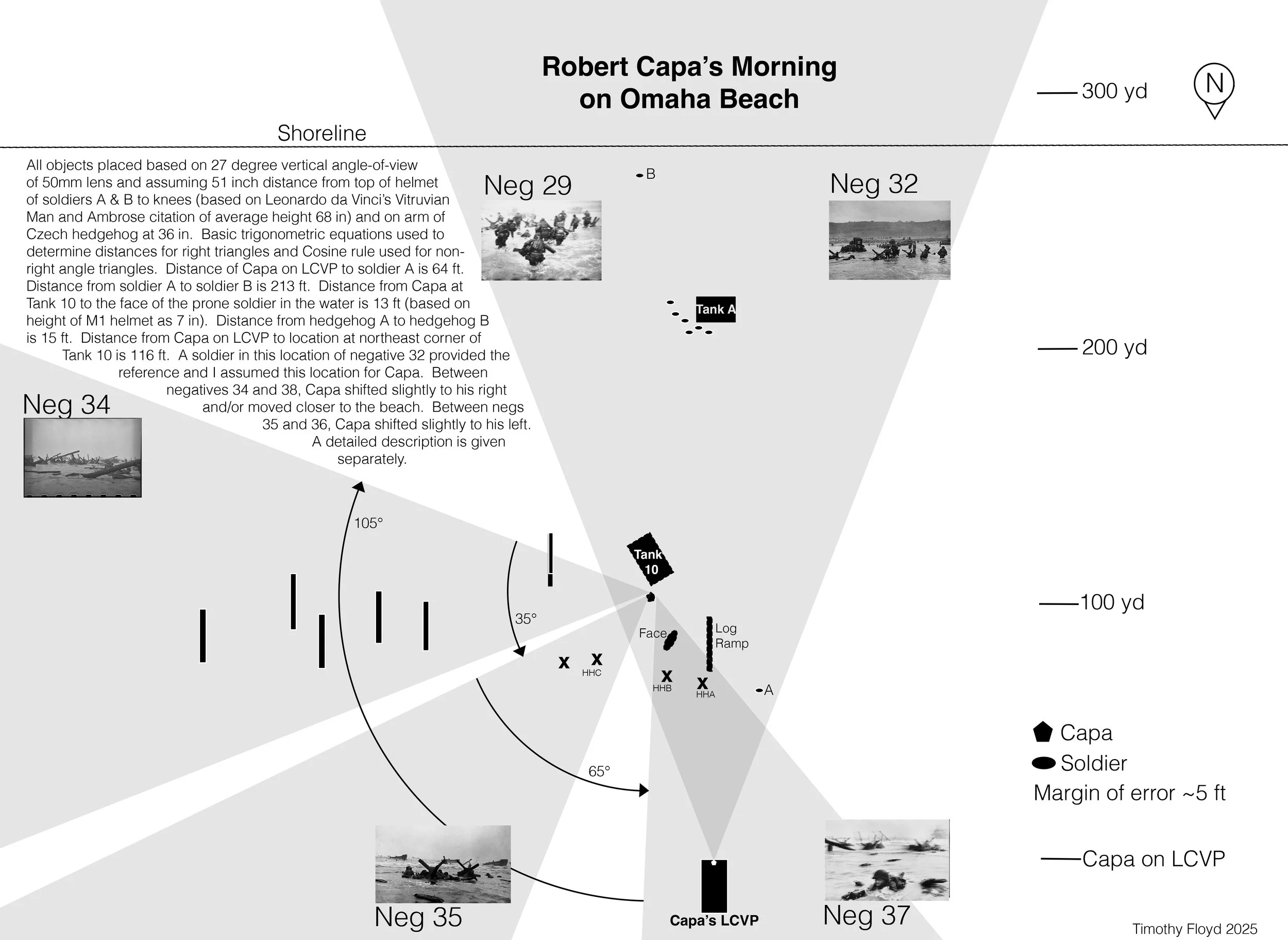

Herrick also "proved" that Capa came in on the 13th wave, based on the level of the water in photographs taken by him and by a Coast Guard photographer, Robert F. Sargent, who was on the beach at 0740 (different section of beach, but ignore that little fact).

I dissect Herrick's analysis of these pictures and the water levels in the post Depth Gauge, so I won't repeat all that here, but I strongly urge you to read it – even now, because it will make the rest of this make more sense. Suffice it to say, Herrick's analysis is flawed and specious on multiple accounts. In fact, a closer inspection of Capa's photographs proves the opposite of what Herrick claims.

So, Herrick erroneously determined that Capa arrived at 0820 with Colonel Taylor, has remained steadfastly pugnacious about it, and dismissed Kays' account and Ms. Sullivan's comments as "stolen glamour," trying to latch on as "parasitic legends."

What a guy. He did a crappy job analyzing Capa's photographs and completely blew off contemporaneous accounts by credible people, essentially calling them liars, then dismissively discounted a daughter’s account of her dad’s activities.

Even writing this now upsets me. Just like Coleman tried to demean and demoralize John Morris, Herrick is doing the same with Kays and Doyle, and by extension, Doyle's daughter.

Coleman condescendingly lectured Ms. Sullivan, referring to Herrick as a "military historian," (which he is not), implying she had better believe the expert, not her own father and the photographic proof.

Both of these men should be ashamed of themselves for their sanctimonious arrogance. They should retract their statements and issue formal apologies to the families of Mr. Doyle and Dr. Kays.

I have uncovered and collated ample proof, through eyewitnesses and careful analysis of his photographs, that Capa arrived on Easy Red roughly at 0740, easily refuting Herrick's claims to the contrary. We know from several eyewitnesses, as well as Capa's own account, that he boarded LCI(L)-94 roughly at 0850. That means he was at Easy Red for 70 minutes.

Having just returned from Omaha Beach, I appreciated that no one could have survived 70 minutes in the water without making it to the beach and taking cover behind the sand dune, on the shingle of smooth rocks at the high tide mark. All of the officers made their men keep moving forward. Colonel Taylor's famous quote about the only people on the beach are dead or about to die was true.

Therefore, the scenario that best fits the information that we have, is that Capa did arrive at 0740 in Kays’ boat with B Company, he made photographs from the LCVP and in the water, he did make it to the shingle, he did take a second roll of film with his other Contax, and it did get ruined by seawater when he waded out to LCI(L)-94.

And, most importantly, William Kays and Lenny Doyle did not lie to their families about their experiences on Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944.

NB: After writing the above, I was able to contact Ms. Sullivan’s husband, Thomas, who confirmed to me that Lenny Doyle saw “the Life photographer” on the sandy beach, taking pictures. In fact, the photographer pointed his lens right at Doyle. This is the first confirmation placing Robert Capa on the beach at the bluff and the shingle. It also strongly supports the existence of the second, lost roll of film, because Capa had already used up his first roll. Granted this is second hand information, since Mr. Doyle has passed away, but it was unsolicited information.

The sand dune and the “shingle,” which is the band of smooth stones parallel to the bluff. Most of the stones were removed. This small area was the only shelter available to soldiers.

*Guest Post 27i on Coleman’s blog

**https://www.historynet.com/robert-capa-d-day-photos-omaha-beach-landing/

***Guest Post 27g on Coleman’s blog