To find out what effect, if any, soaking in seawater would do to exposed but undeveloped film, I experimented on a freshly exposed roll of Kodak-XX 5222. I chose XX film because it succeeded Capa's Super-XX, which had been discontinued in 1958. I don’t have a Contax II, so I used a period rangefinder camera, the Leica IIIc.

Kodak Super-XX 35mm film. This is the film Capa used on D-Day. Kodak discontinued this film in 1958.

I added sea salt to tap water to make a 3.5% solution (average salinity of seawater), dunked the exposed cannister of film in the solution for 20 minutes (assuming the maximum amount of time Capa would have been in the water during his exodus), let it dry for 36 hours to simulate the time before Capa’s film reached Life in London, and developed it normally. I did not put it in a heated drying cabinet; it air-dried in a shower stall.

I had always heard that saltwater can be used as a fixer in a pinch, meaning it removes undeveloped silver ions from film. If it hits film prior to exposure to the developer, it should remove most of the silver. So, I fully expected to see relatively clear negatives that would have a washed out appearance, not dark and mud grey.

The results were surprising. First, the film felt dry and rolled onto the spool without difficulty. I imagined that it would still be wet, or the emulsion would be sticky, making it difficult to load the film. This would have tipped off Wild that something was wrong. But not so. It felt like normal, dry film.

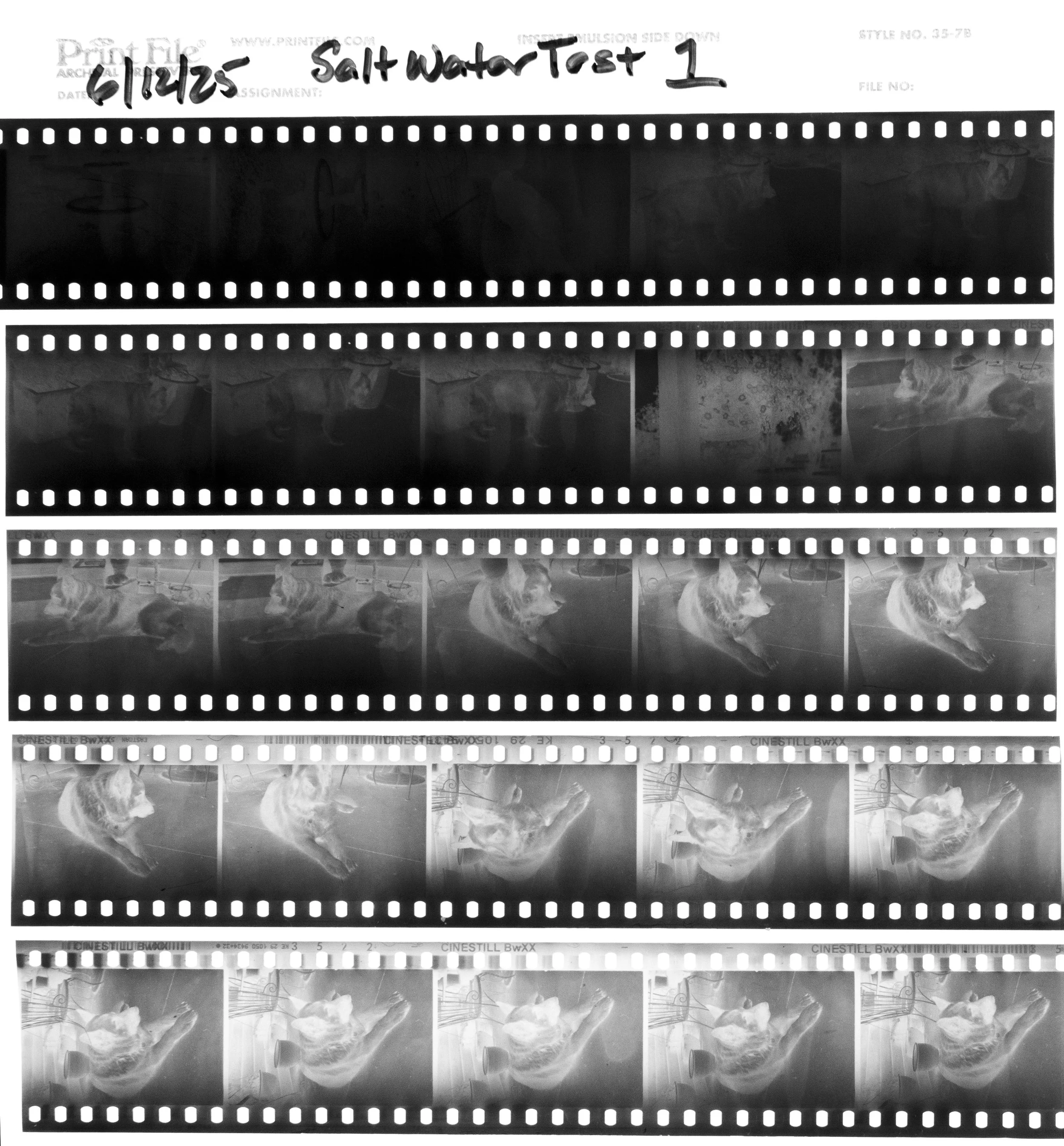

Negatives from the first test roll, Kodak 5222 XX film respooled by CineStill, Inc. The cannister was submerged in 3.5% saltwater for 20 minutes and then placed on its end opposite the nipple for 36 hours at room temperature to dry. Normal processing in CineStill Df96. The uneven effect of saltwater exposure had the least effect in the later frames, which were closest to the spool. Also, when drying it rested on the end opposite the nipple, which would be the bottom of these frames. This indicates that the modern cannister was tight enough to prevent complete saltwater intrusion after 20 minutes. The fogging effect of 20 minutes exposure to saltwater appears overexposed and results in a "grey mud" appearance, exactly as described by John Morris.

Immersion in 3.5% sodium chloride for 20 minutes, followed by air-drying for 36 hours, resulted in precipitation, not removal, of metallic silver throughout the emulsion that had contact with the saltwater. It did not wash away or distort the emulsion. It did not prevent development, in fact it looked like the saltwater developed the film. It had the appearance of over exposure to light, as if Capa had removed the back of his camera without rewinding the film first.* It looked like, well, grey mud.

Plain water does not do this. It is common to soak film in plain water prior to developing, with no adverse effect. There must be something about saltwater. Film contains molecules of silver bromide, AgBr, in the gelatin. Bromine is a halide. Saltwater contains sodium chloride, NaCl, and the chloride is also a halide. It’s not in plain water. There must be some exchange of halides occurring with film in a solution of sodium chloride that allows the silver ion to precipitate as metallic silver crystals. But I probably need to talk to a chemist about that.

I think the uneven effect on my roll was due to incomplete saltwater exposure. I think the cannister was so light-tight that it was also pretty water-tight, and it did not fill completely. The areas that are dark correspond to where I would expect a limited amount of water to be located.

I repeated the experiment, but this time left the film cannister in saltwater for 4 hours. This did give me the results I originally expected, washed out negatives. The saltwater had fixed the second set of negatives. I guess whatever process occurred during the first 20 minutes was reversed by the persistent exposure to sodium chloride. I definitely need to talk to a chemist.

Contact sheet of film submerged for four hours in saltwater. Most of the exposed silver ions in the emulsion were bleached out by prolonged exposure to saltwater prior to developing, resulting in negatives that appear underexposed.

My interpretation, is that the 20 minutes that the second roll of film spent submerged in seawater, in Capa’s pocket or camera bag, was sufficient to fully soak the film in 3.5% sodium chloride. This was sufficient to cause the silver ions to aggregate and then convert to metallic silver when developed. The cannisters he had may have been less water-tight than a modern cannister. After he boarded the LCI(L)-94, the water drained out of the cannisters. Thirty-six hours later the film was developed with identical results as I obtained, only his entire roll was soaked, whereas only part of mine was soaked.

This resulted in the dark, “grey mud” appearance of the negatives, that poor Dennis Banks interpreted as due to his negligence.

No one lied. Not Morris. Not Capa.

Clan Coleman would have you believe that Robert Capa and John Morris conspired to create a complex lie to explain Capa’s dearth of images from Omaha Beach, while maintaining his daring persona. They apparently intimidated all Life employees who witnessed the event into lifelong silence. And they were able to hoodwink subsequent, multigenerational employees of institutions, authors, famous CNN hosts, bloggers and YouTubers into, not just accepting these lies, but perpetuating them.

On the other hand, I have shown it is much more plausible that they simply told the truth as they saw it.

* Over exposure to sunlight is my second theory explaining the ruined roll B, in a subsequent blog post, Overexposure.

Ed: Corrected “sodium” to “chloride” when describing halide, 5/30/2025.